This is Le Pre-Saint-Gervais, 4.6 kilometers from Paris, which has the distinction of being the 8th densest city in the world, despite having a population of only 18,121. Unfortunately it is not a medieval city; Paris annexed the commune in 1860, whereupon it was completely transformed from a farmland and royal resort into the densely populated suburb it is today. So it cannot be representative of any sort of medieval city.

What it can tell us is something about population density. Unlike the sort of slum that is the substance of Manila, Mumbai or Dhaka, Le Pre, along with other French communes like Levallois-Perret, Vincennes and Saint-Mande, is a structured, architectured environment. In that way, we can compare it to the densely made cities of the Middle Ages, as a limit on what might be termed as maximum population density might be. Le Pre has a density of 259 persons per hectare. In old English units, what my world is based on, that's 109 persons per acre; or rather, per 43,560 square feet; and, just for shits and giggles, 109 persons per 2,007 combat hexes (that are 5 ft. in diameter, 21.7 square feet in size).

That will seem empty for most people, and it will surely occur to many a reader that population densities in history MUST be more dense than that. Truth be told, we can argue whatever we want. There are no sources; no final documents; no definitive arguments at all, for what population densities might have been at any time of history except in our own time. And the reader will take note on how much green space and open road, without visible cars, occurs on the map above. Too, the densest city in the world, Manila, is only fifty percent denser than this. Picture the above with only one third of the greenery removed.

|

| Google Earth's 3D Rendering of Le Pre-St.-Gervais |

Where it comes to exploring an urban environment, we might think in acres ... or, more appropriately, "blocks." A block is the standard description of the city environment; it comprises both the street and the buildings, it suggests a certain character and, best of all, it isn't used for any other term to be found in Dungeons & Dragons (or any other RPG that I can think of).

But how large is a block? Well, I have a document for that too, that the reader can use to while away some time at work while looking like doing real research. It talks about "block density":

Now, this talks about Georgia in America, but let me stress again that there are NO source documents from any time that are earlier than the 19th century, so it doesn't matter if this is factually true for the time in which a D&D game might take place. We can, in the end, just make shit up; in the meantime, however, let's just go with what documentation we have."All streets at some point form blocks (a block being defined as a street that closes in on itself, or an area of private property surrounded on all sides by public rights-of-way). Blocks can be relatively small. In the Fairlie-Poplar district of downtown Atlanta blocks are 200-feet by 200-feet. But blocks can also be relatively long, like some of those in Manhattan with a 900-foot length. In either of those cases, you have a different kind of block density, and certainly a different kind of block density than what you typically find in a place like Alpharetta, Georgia, in the Windward area, where the blocks take on an entirely different magnitude of size and amorphous configurations."Blocks can be difficult to measure because they are not all rectangles. Some are trapezoids, or circles, or amoeba-shaped. Many residential areas here in Atlanta have these sort of amoeba-shaped blocks. So you have to start teasing out some of the geometric properties of these things such as block length and depth and total perimeter in order to compare them."A number of years ago I became interested in this type of analysis and this question of block density. I began a little study which is only semi-scientific. I say semi- because at the moment it only includes a sample size of 200: ten cities, 20 blocks per city. I have compared the sizes of blocks built before 1928 to those built after 1928. Why 1928? Because that is the year that the Standard City Planning Enabling Statute was passed out of Congress, and that is when we have subdivision regulations being adopted in a formal way for the first time in almost every city and county, every municipal jurisdiction in the nation."

I think the stress that we can get from Douglas Allen's research is that blocks change from place to place, and from time to time. Our conception of blocks is based on regulation and municipal law, that was once not a part of the community's mindset. As shown on Allen's table to the right, block size has increased since 1928. Allen's argument is that the growth can be ascribed to the presence of automobiles ... and to traffic signals, which were designed to compensate for a speed of 40 miles per hour. It's an interesting passage, but I won't go into it here.

For myself, I quite like this. The actual dimension of an actual city block is not important, from a game design perspective ... but identifying a hex as "the amount that can be explored in a day" with "one block" is appealing. But of course, how big of a block are we talking about? One that fits with a city like New York? Or something more akin to Omaha?

The answer is bound to be arbitrary, no matter what we base the decision upon. None of us can possibly know if it is possible to explore 1.9 acres in a day or 4.4 acres in a day, given what a medieval town might look like. It might take us ten minutes to cross a particular thoroughfare because of traffic, the amount of gong on the street, our willingness to get ourselves caked with said gong or how wide the street is. There are a hundred possible drains on the clock that we can't conceive of or guess at, but can reasonably be taken for granted as we have made our environment as convenient as possible, for everyone (by including street lights, for example). Getting around in a Medieval city might have been a real headache.

Still, we have to base these things on something, right?

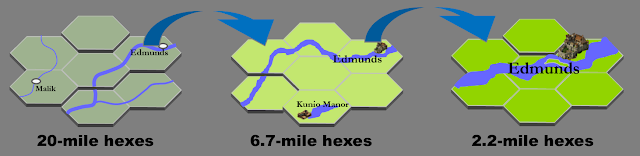

Some will remember that I map my world in 20-mile diameter hexes, and that I have occasionally spoken about breaking up these hexes into smaller units.

If I continue to zoom in, to produce progressively smaller hexes along this process, always dividing one hex into seven smaller hexes, I get the following chart:

Which, I'm sorry, fascinates me endlessly. In the middle of the chart, we find the sweet spot: 3.76 acres, with 225 people if we establish a dense population as 60 persons per acre. Some block-sized hexes could be relatively empty; so that there's no absolute size for how many hexes a given village, town or city covers. A village made of only scattered houses may cover a dozen block-sized hexes. A densely packed town on an island may cover only five or six blocks. This makes for plenty of creativity.

Nor does a town have to be in one part. Three blocks along a river might be separated by empty hexes (fields, rough ground, cliff faces) from two dense blocks surrounding a castle. We don't have to be regular in our design, such as we've seen from pre-made generators.

I also love the fact that the chart goes right down to the combat hex, 5 feet across. If any readers have ever used a typical rubber mat for game play, those are usually 48 hexes by 32; the town block as depicted is 87 combat hexes across. That would be four battle maps. Well within the realm of grasping size and scale here.

Fascinating, nyet?

I think it is interesting (and telling, for your game) that pre-1928, a block had a fairly similar size across cities, but after the 1928 bill (and the automobile), the variance increased greatly.

ReplyDelete