It should be evident that I'm pursuing the directions east and west more than north and south, because there is more east and west to the shape of the world. Thus the map is only 6 hexes higher but it's 12 hexes wider. The size of image is 55% of normal. It can be seen that I reached the Black Sea on the east, completed much of the Danube River's course and nearly completed the swamp around Dobruja. Much of the northeast corner now extends into the Ukraine, while the southwest is verging into Serbia. The heavily populated core of Transylvania is nearly enclosed; I think the map gives good evidence of how the region formed an isolated power-centre in European affairs, given that it's essentially a fortress between mountains.

Tuesday, May 31, 2022

The June Version

It should be evident that I'm pursuing the directions east and west more than north and south, because there is more east and west to the shape of the world. Thus the map is only 6 hexes higher but it's 12 hexes wider. The size of image is 55% of normal. It can be seen that I reached the Black Sea on the east, completed much of the Danube River's course and nearly completed the swamp around Dobruja. Much of the northeast corner now extends into the Ukraine, while the southwest is verging into Serbia. The heavily populated core of Transylvania is nearly enclosed; I think the map gives good evidence of how the region formed an isolated power-centre in European affairs, given that it's essentially a fortress between mountains.

Saturday, May 28, 2022

Wildered Wildlings Wilding the Wildness

|

| Verticle axis increased 2:1 |

I live on the edge of a wilderness, a happy place called The Rocky Mountains. This is the country about 65 miles east of me. People come from all over the world to see these mountains; and naturally, when I have friends drop 'round, a trip to the mountains is always on the iternerary. Yearly, in every season, like clockwork, people go out into these mountains and die, mostly from failing to take along sufficient equipment, underestimating the distances and the difficulty of terrain and ... occasionally ... because they try to use their cell phone as a flashlight so they can walk out at night, running out their battery and making it impossible to triangulate their position.

|

| No, no, no, no, no. |

A Test Proposed

Friday, May 27, 2022

Counter-duality

Coming back to worldbuilding.

Let's put all the detailed structural work surrounding geography, politics, sociology and such upon a shelf today and talk about "function." The world is a setting where things happen, but the world is also a tool designed to be practical and useful for game purposes. The goal is to get the world up and running so that it's applications can serve both the DM and the Players, and other aspects of the game aside.

As a DM, I need the built world to provide me with inspiration at a glance whenever I need it, specifically during the course of the game. This means that if I look at a map, that map is constructed in a way that upon looking at it, answers to questions and possibilities emerge within a few seconds, leading me to present situations for the players that I may have had no thought of 60 seconds prior ... but which some part of the work and preparation I've done regarding building my world has just provided.

Let's take a familiar example. A dungeon room is a highly recognisable D&D construct. Most DMs, having the map of a dungeon at their elbow, can visualise a number of monsters that could be placed on the fly in that dungeon room; what they're doing in the room is fairly evident as well, since there are only a few things that a group of orcs, say, or an ochre jelly, can possibly be doing as the players arrive. While the structure of the dungeon is limited, that structure provides a clear-cut functional purpose. The players are here to fight, they're here to find things in the room, they're here to seek passage to the next room.

If I take a random dungeon map, say the sort that Dyson regularly creates, as experienced DMs we can reason easily what ought to be there and, as the game session begins and gets going, the shape of the walls, the small incorporated details, whatever beasties we've inserted and so on sets in motion a fertile degree of invention ... one that we're used to because dungeons are such a large part of our gaming experience. Plock any dungeon graphic in front of a DM with a mere two or three years of experience and running a single session without notice is not a difficult task.

Unfortunately, DMs tend to rely so much upon dungeons that they gain little experience with other possibly functional locations. For many, a town encounter fails to produce an adequate experience because there are NO comparable, useful resources on par with what a dungeon layout provides. Likewise with a wilderness or an occupied rural landscape. This disconnect occurs because such places are not structurally limited like a dungeon. A village or a town dictates that virtually anything that's done will be observed by someone, since these places are full of people; and if the act is observed, it's bound to be reported. Many players, comfortable with doing whatever they want in a dungeon, suddenly become stymied by the lack of "freedom" a town offers.

And that itself is a strange happenstance. We might suppose that the dungeon is the constrained environment, but it's not. The consequence provided by a dungeon is whether or not our side can win in a fight ... whereas the consequence in a town is usually the recognition that if the whole town turns out in force, we're definitely going to lose. Let us fight 20 orcs and not a hundred guards.

Taking the wilderness, it's a question of exposure. Fight those 20 orcs in a dungeon and afterwards we can spike the doors and make our retreat, confident that once we're outside the orcs will lose our track ... and if the DM isn't the sort to hurl wilderness encounters, or run a strictly wilderness outdoor adventure, we're "safe" as soon as we get outside. But if, when we're outside, a monster of any size, and particularly of great size because the outdoors gives lots of room, attacks us while we're recovering, um, we're fucked. Players who lack experience with long-term outdoor situations also lack knowledge of how to protect themselves, while DMs who also lack experience tend to think the only thing one can do is throw large beasties as encounters.

In short, a dungeon seems rich and full of possibilities, while other parts of the setting feel repetitive and the players excessively vulnerable. In response, many DMs choose to discard any conflict in towns altogether, along with any use of wandering monsters in the wilderness. It's simply easier to ditch these adventure ideas and get the players out to the dungeon, where the DM is happier and the players as well.

These are setting-function deficiencies. Because DMs have never been taught or even seen another point of view, they tend to perceive every setting in terms of the dungeon's combat-puzzle-trap model. Or they turn to the dualism that if the game isn't combat, it's role-playing ... so that town encounters become long drawn-out chat exercises, where most of the party has no idea what to say and everyone is worried that saying one wrong thing will land everyone in loads of trouble. This IS possible; there's no pretending it isn't. But likewise, it's just as possible to make one incredibly stupid move in a dungeon and be in loads of trouble. It's only that most of us have seen what those stupid dungeon moves are ... whereas we have next to no idea what they might be in a town.

Moreover, as DMs want to stress the importance of role-playing in their campaigns (if they're the type), they will up the stakes with every conversation until we're at the baker's, ready to draw our swords while discussing the cost of a dozen biscuits. Overmuch ballyhooing is the bread-and-butter to many a role-playing DM, struggling to assign tension and difficulty where, in fact, there ought to be very little. Most conversation isn't, and shouldn't be, stressful. It should be interesting, full of enlightening details and suggestions for social and status advance ... but my own experience has shown that even if my foot isn't on the gas, the player's will be automatically. Time and again I've had to explain to players that nothing bad is going to happen if they trust someone. This is clearly a taught habit, as multiple DMs in the player's past has taken advantage of the player's trust at every opportunity.

The approach to role-playing, again, pushes the players back to the dungeon — where they need only worry about bloodsucking monsters and insidious pendulum traps. Thank gawd, we're back where things make sense!

Caught between the game being either a dungeon crawl or an uncomfortable chat with townsfolk, it's difficult for most to glance at a map like the one shown and come up with anything except, obviously, to visualise a dungeon located near Reni or Macin or Ibraila. The rest is a smattering of places and names, without a sense of "D&D" going on.I've touched on this element before, but it's worth repeating. The dualism of the dungeon/role-play model is that BOTH place the player firmly in the passive role, waiting for the DM to do something that makes the game go. The players wait for the next dungeon room. The players wait for the other side to start the conversation that decides what the players will do next. And the players, used to this functional structure, dutifully wait to be told what expectations have fallen upon them. "I need YOU to go to this dungeon; I need YOU to fetch this object to me; I need YOU to rescue the princess." The players are a foil in the hands of the DM, who arranges the targets, or obstacles, for the foil to overcome, all the while being in full grip of the foil's handle. The players get the delicious promise of being the tip, the part that actually touches the enemy; the part whose whirling around in the air feels exciting. But all the while, the tip possesses no actual control; the control is in the DM's subtle wrist.

Plenty exist to argue this ought to be the case, both DM and Player. Virtually every player has experienced only this form of play. And having had only one sort of experience, it stands to reason that players loving the game would argue against a change. After all, they don't know what they'd be getting.

When I look at the map, I don't see a passive experience for the player. Given sufficient wealth, time, freedom from responsibility, freedom from worrying seriously about death — all of which is the player character's perspective — I see a place where I can freeboot around as much as I please, witnessing and personally experiencing the local culture, making arrangements, bartering, intervening as I please against any wrong I see and always confident that my escape is assured ... as planning my escape comes before taking the hazardous step to intervene. For every enemy I make I'll be sure to make three friends ... and if I am a player in this location where the DM is a fellow like myself, then I have every reason to believe my friends ARE friends, and not a trick of the DM who cannot keep his hand off the foil. I see half a dozen opportunities in the map for plunder, investment, piracy, trade and settlement ... with plenty of wilderness to clear out mere footsteps from my front door. That is, wherever I happen to put my front door, which might be anywhere.

Freed of the worry that I might say the wrong thing in a "gotcha" campaign — as these are just people and I've spoken with people all my life — and equally confident of defending myself in a wilderness, I'm not beholden to the DM's instigation of a pre-planned campaign ... nor do I have to approach the DM to beg him to run such and such a module because I'd like to run in it. I will, thank-you, write my own "module" on the fly, because I think I can do a better job.

And taking the DM's perspective, all the opportunities I've just cited are there: the little village run by an petty overlord, the lake monster that needs killing so the barges can roll past safely, the beach where the players can lie in wait for a small river craft to seize, the hamlet they can pillage before making haste to another part of the marsh, the dock they can have built, the smuggling in which they can partake, the bay where they can build their lair and so on ... and of course, if it's really necessary, the half-drowned dungeon they'll find somewhere in this part of the world.

The map gives me this; the little symbols on the map as well; the perspective of how a world works; and the readiness to let the players do as they like without arbitrarily restricted their behaviour on any account. This is worldbuilding to me. Every part of the human experience laid out, good and bad, with clues baked right into the design that I can see clearly and reveal to the players as they set out to explore.

Sunday, May 22, 2022

Exorcising My Thoughts

Today I'd like to start by clarifying this post from May 5. When I say I'm so tired of D&D, I mean content such as a channel like "Master the Dungeon." The proliferation of gimmicky shortcuts masquerading as "real advice," similar to the way that relationship gurus give short cut advice like dumping rose petals on a bed. A fellow can spend a lifetime explaining why this stuff doesn't work and why it's poison for the community, but it's an enormous waste of time. I don't want to do it any more.

This does not mean I want to stop talking about my campaign, my game structures, my wiki or other material associated with the game I play. It should be evident I'm still writing about D&D. Only, I'm interested in rebuilding my approach to appeal to those specific readers who connect with the expression of D&D that I embrace. That's all.

Yesterday, Sterling brought up some points I'd like to address first. I'd like to start with the middle suggestion: a new voice that might be more attractive to new readers.

A "new voice" is a tricky affair. As a professional business writer, I adopt a structured, passion-free voice that carefully provides data without saying anything firmly. Such-and-such company "expects" to do well in the upcoming quarter, as we are "committed" to our "goal" of "world-class process safety performance." We "recognise" the "importance" of blah blah blah "performance," etcetera, etcetera. It's an effort to sound like we're saying something we mean, while absolutely choosing words that say nothing and which commit us to nothing. I can find the same language applied to D&D all over the internet, where advice is given without definitely stating that this advice will achieve anything.

But "the speak" is very appealing. It sounds encouraging, it sounds like investors have good reason to trust the company, it sounds like viewers have good reason to think these presenters really know their stuff about D&D. The trick of writing this way has been around a long, long time. The way it works with my job is that we each make a first stab, then share the writing around to help each other "clean it," which is the phrase we use. "Cleaning" means getting rid of anything that might conceivably say something concrete.

What doesn't appeal to investors is anything that might cause them to lay awake at night. You consider: you've got five million invested in a company that makes safety equipment and you read on line twenty seven on the fourteenth page one moderately negative word related to government-mandated evaluation curtailments in the lower commodity price environment. Wait a moment. What was that? Why is that there? You can already feel your palms sweat. People read about things they consider important because they want to be reassured. They want someone to tell them it's going to be fine. This is the fundamental reality of writing for anything "official" — quarterly reports, a business magazine, a foody channel, a website that sells clothing. We are here to make the reader feel better about something the reader already believes. It's Grognardia's approach, it's Tim Brannan's approach, it's Justin Alexander's approach. These guys know what they're writing.

At the moment, science is undergoing a decades-long "replication crisis." Essentially, many findings in the fields of social science and medicine aren't holding up when others attempt to repeat the experiment. What's especially interesting is that many inside the science publishing industry say that they can recognise which published findings are likely to be supported and which aren't — but that "non-replicable" papers are published anyway because the results are more "interesting." In short, the problem with what was once a reliable scientific process — "publish a paper, encourage others to repeat the experiment, move science forward" — is being subverted by the business of publishing. Publishing, and the interest it provides to eyeballs, is more important to the science magazines than the science. Thousands of hours of research time are being wasted trying to replicate experiments that have no chance of being replicated. That wastes time, it wastes money that could be put towards more fruitful ventures ... while the hired business manager of the science magazine, who is not a scientist, is more concerned with ad sales than with human advancement. This is a problem.

When looking at the words, "more attractive to readers," these are the pitfalls that roll through my head.

I can be much more attractive to "readers" if I begin to rant all the time. The more fire I spit, the more readers I'll accumulate. It's a fact. Any time I let myself off the chain, even a little bit, my readership jumps 50 to 100 percent within a few hours. I'm rewarded for being a raving lunatic. But I'm rewarded with the wrong kind of readers. I'm rewarded with cranks and deplorables, voyeurs and people who really don't give a rat fuck about D&D or any legitimate role-playing. Specifically, bored people who like their blood being stirred. I don't want to chase these readers any more.

So if we're talking about my being more attractive to readers, what's wanted is more attractive to a specific, I-want-to-do-hard-things kind of reader ... which, in point of fact, dislike it when I rant. So, as I've known for more than two years, stop ranting, Alexis.

Difficult. I am a fervent, zealous advocate of intelligensia, productivity and respect for quality. I'm easily infuriated by misinformation for the sake of self-aggrandisement, appeals to emotionality, pandering language and flat out lies. For example, just now, mention "abortion" in my presence and get ready for a violent, angry, impassioned tirade about man's inhumanity to women. This is what I'm like when I'm free to express myself ... which I'm not free to do on the internet, though gawd knows I've tried. I'm not the sort of protestor who allows the cop to quietly lead him away. I'm the one at the front, screaming at the top of my lungs into the cops face, ready to take his baton away and have a go. I don't publicly protest any more because I know I'm going to get killed doing it.

When I write material for money, I have to hold my nose. I've lots of experience. I know how. But here, on this blog, I don't want to type on a desk full of shit. I want to say what I think needs to be said.

My goal is to say it patiently and respectfully. But not attractively. I've been working on that. I think I'm doing better year by year.

So ...

Dropping the moniker. Stop calling this blog Tao of "D&D." It is true, the specific system — except that it's mine — has ceased to be relevant and I no longer wish to talk about one system vs. another, or any system except mine.

Why not change the blog to "Authentic Role-playing" or "The Other Role-playing Game." I could make The Higher Path public and write there. Leave this blog up as a reference and go elsewhere. Because I would have to do that. Blogger has it set up that you can't change the blog name, at least not on the url. The banner at the top might reader TORG, but the blog will always be "tao-dnd." Plus, there are scores and scores of other blogs who still have me listed as Tao of D&D, whether I change this blog or not. Changing to a new blog means pushing a lot of supporters to work on my behalf ... and quite a few links to blogs that are no longer being updated would forever send readers to here, and never to the new place. The same can be said for people who connect to my Patreon page, which is also titled The Tao of D&D. It's not that easy to pull stakes and move. There are consequences.

Plus, I get readers who arrive here because they're looking for "D&D." My two most popular posts, and ones I still get weekly readers for, though they are 11 and 9 years old, are "How to Dungeon Master" and "How to Play a Character." While readers fall away from me for various reasons, including that they quit playing D&D and therefore quit reading about it, these two posts continue to drive new readers into my orbit. They read the big long post, wonder about what else I've written ... and some of them begin reading the entire blog from the beginning, all 3,400+ posts of it. And I don't write short posts. The words "Dungeons and Dragons" and "D&D" most likely appear more than 10-15 thousand times on this blog; I doubt I go more than two posts without using the moniker.

I think, realistically, it's too late to "drop it." Like a franchisee who runs a string of successful MacDonalds, who has to facepalm every time the Mac commits some horrible evil in the world, I'm none the less locked in with my devil.

At the same time, not to appeal to anyone's emotions, I like "dungeons and dragons" as a brand. Maybe it's not my brand, but I can say with assurance to someone in the real world that "I play D&D" without getting a load of judgement and edition diction on the subject. The only responses I ever get back are, "Really? I used to play," or "Really? I always wanted to play." Oh, and occasionally someone doesn't know what it is. Very, very occasionally. That's something that's changed.

Finally,

I have no faith at all in a discussion platform. A "discussion" requires more than one voice. I'm so intimidating, apparently, that the only possible discussion that would ever take place in an environment like that is one I wasn't a part of.

People want to be right when they say things. I have no problem with that, I want to be right also. But I want to be right because I AM, because I've done the research and I'm channelling the words of other people talking about things those people are experts in. When my rightness is challenged, I go full Greek and begin defending myself with arguments, which come fast and furiously and loaded with lots of words, written by someone trained to write words. As Oliver Platt put it in the movie Chef, I buy ink by the barrel.

Other people want to be right because "they have an opinion too," or "Why can't you consider my point of view; it is because it's not yours?" If they would only back up what they say with Shakespeare or Mills or Sartre ... or somebody ... but they don't. They can't. They only know how to assert their humanity, which puts their argument on a par with a farmer in the Stone Age, who was also human and also had not read the works of Shakespeare, Mills or Sartre. It's the kind of thing that makes an intransigent, inflexible elder, me, willing to hit the impertinent little poster remarking on the subject at hand.

It is unfair and unrealistic of me to expect other people to educate themselves and acquire personal experience about the subject matter based on WORK DONE rather than CONJECTURE before commenting on my blog post about mapping, worldbuilding or whatever. It's anti-democratic. Keeping in mind that "democracy" is based on the Socratic method, which we can define simply as beat the living tar out of your opponent by employing rhetoric, mocking jokes and as many arguments as can be drawn while the dupe stands there and tries to reply. In this case, "anti-democratic" means that expertise is irrelevant, knowledge is irrelevant and experience is irrelevant. All that matters is that I have an asshole, you have an asshole ... we can agree to disagree.

Damn. Caught myself ranting again.

Sorry.

So, yes, I have this fantasy of twenty people sitting around talking about cool stuff and building an awesome collaborative, functional roleplay structure through hypothesis, experimentation, observation and conclusion, followed by replicating the experiment between us ... but I live in the real world. And after the failure of several attempted collaborative adventures I've tried to launch these last 14 years, I'm not falling for that football again, Lucy.

This has been a good thought experiment, Sterling. I think my writing is fairly sustained and motivated. I just want to do it in a way where I don't experience exhaustive self-reflection when setting myself the task of writing something that I know will bore most readers who chase other expressions of D&D. I want to feel secure enough to be boring. To write as long about maps, worldbuilding or any other subject, without feeling the need to simplify it for the yokels, while ceasing to worry that I've been at this awful, boring subject too long. Something that seems to be evidently true because it's been five, six posts and fifteen days since getting a comment.

The comment section is brutal. On the one hand, I want to strengthen myself to believe that a lack of comments DOES NOT MEAN no one is interested in what I'm writing. I mean, at my job, I get regular comments from other writers, I get feedback from my boss, there's definitely a back and forth that goes on with predictable regularity. If the answer I get when I submit something is, "Yes, I read it," and that's all, I know my boss has no problem with it. I did a good job. But there is no personal contact through the comment section, not for me. Which relates to the intimidation problem.

There's another angle, too. By grade 12 in High School, I'd left the football team, where I wasn't that popular, and I'd bailed out on most things ... and I was always something of a misanthrope, except for my D&D friends. And then I met this girl. This remarkable girl. This girl whose father was a diplomat in Singapore, where this girl had been living for five years, in an intense urban culture that was very much not the hideous suburban culture in which I lived. She loved my nature. When we connected, it was fiery, violent, hot-blooded. It was a consuming, frenzied relationship that lasted for more than two years.

And when her new girlfriends at school — people she met at the same time she met me — demanded to know why she had any interest in dating that geeky psychopath Alexis, this girl didn't give a damn what my reputation was. That's what made our relationship work. It was based on what we felt. Not what other people felt.

There are definitely people out there who don't want to admit to their respect for me, or engage with a post I write, but who do READ me, because they are worried what other people will think of them. They are worried what they'll think of themselves. Because they will never forgive me for some things I wrote ten or more years ago. Never.

Which is why I've considered burning the comments section. If people can't comment, then I can't expect them to comment ... and perhaps I can write as much boring stuff as I please without worrying what anyone thinks. In reality, comments aren't important. The only important number that exists in my world is my Patreon support. It really is the only comment that matters.

But, personal forces in my orbit, especially my daughter, believe that removing the comments would be the death knell for this blog. They're probably right. I'm probably thinking about this thing too emotionally. I should just suck it up and be boring. And stop fucking worrying about it.

Saturday, May 21, 2022

My Readers

If I'm to consider why I'm writing, it follows that I should give thought on whom I'm writing to. What is it that makes a reader of mine? And, consequently, the sort of person who seeks a rigid exploration of self through a process of aggravation, difficulty and the accumulation of pride ... as these are the games I strive to run. I ask my players to track their movement in combat, to track how much they're eating and their encumbrance down to a tenth of a pound. I ask them to accept stark limitations on what they can do, I expect them to maintain a standard of interparty decency and a firm grammatical presentation when explaining their character's actions. I do this in the spirit of behavioural rules surrounding games like golf, chess, bridge ... and even professional baseball, which dictates exactly where and how a pitcher can stand on a mound before delivering the ball to a batter, whose play is based on an exact imaginary square in the air that the pitch must be "inside" or else counted as a "ball."

Why do my players tolerate this? And why do I have readers who acknowledge that this is important ... especially when we know quite obviously that many D&D players would find this absurdly anal and very definitely "un-fun." Having to play according to these ordinances, why is it my players nevertheless laugh quite a lot, and clearly have a very good time, and return to play the instant I ask them?

I think it's relevant to examine why some people drive themselves to do hard things in the first place. For example, with no expectation of ever winning a competition of any sort, an individual decides they're going to run an official marathon race, 26 miles and 385 yards, in 3 hours and 30 minutes. This is no where near the record for a marathon, which is currently 2 hours, 1 minute and 39 seconds. Yet to accomplish the feat of running the distance in 210 minutes, the runner will begin to train for at least a year ... on top of many years of training prior to that in order to run a marathon at all. This "advanced" training will demand running distances of 35 miles a week, and even more in the weeks before the event takes place. He or she will need to achieve a "comfortable" rate of 8 minutes per mile, for mile after mile, to meet the task ... and then, during the race, he or she will have to push harder than that. Harder than ever before.

What for? What's being gained? The training is hard. The race is hard. And potentially, the goal may not be reached. The runner may only manage the marathon in 3 hours 40, or 3 hours 35. Why does he or she not feel devastated? Why does it make them want to train more, strive harder, achieve that goal the next time? And why, after reaching 3 hours 30, the runner wants to try for 3 hours 20? What's going on here?

When we listen to people who "love D&D" talk about how onerous it is to have to account for their equipment and calculate their encumbrance, why is it so many people nod their heads and agree, asserting firmly that calculating encumbrance is a "waste of time" because it's "so time consuming." We can suppose they don't see the benefit in keeping a record; but my personal experience with players unused to managing encumbrance usually chafe at the lack of material items or how actual calculations slow their characters down in a fight ... much more so than the actual trouble it takes to add and subtract numbers. Yes, it is a fact that making records of this kind does require a few minutes and often a calculator ... though my players often employ a computer and a spreadsheet, so that the instant they record an item, the total weight is instantly calculated also. The difficulty is not really the accounting, though this is often the excuse. The difficulty is the rigid control this places on the character's things and movements. The limitations. The making of a part of the game hard that used to be very easy, since we weren't accounting for how fast we moved or how much we had.

Take away these easements, however, and the player quickly feels bound by every choice they have to make in purchasing items, in a way that has nothing to do with how much money they have. Many, many cool, awesome things they'd like to have along are suddenly too heavy to get. And since they usually have those things when they play in campaigns that don't record encumbrance, it feels "unnecessary" and "unfair" that they can't automatically have those things now. It doesn't fit their worldview, such as they've developed it over time.

Think of any activity we don't ordinarily do — say, marathon running. Imagine that someone else with the power to make us pulls us out of our comfort zone and forces us to head out and do 300, 400, even 500 minutes of running every week. They start us out by enabling us to walk, but they keep pushing us to run for as much of the time as we're out there moving. We'd resent that. We'd resent the time it was stealing from the rest of our lives. After all, if we wanted to go marathon running, we'd do that.

But if our minds were open, and we were kept at it for a few weeks, we'd notice some changes. Health, for one thing; we'd feel tired, but more limber getting up in the morning. We'd notice some of that fat being winnowed away. Partners and friends would remark on our "looking better" and we'd like that. Oh, we might say something bitter like, "I ought to look better, given how fucking hard I'm working," but we'd like the comment all the same.

We'd notice other things too. Three or four weeks in, we'd notice that it's actually easier to spend 90 minutes running. It isn't actually easier, of course; what's happening is that we're stronger ... but it seems easier from our perspective. Six to eight weeks in, as we're huddled out to do our forced run, we'd have stopped griping and worrying about it. What the fuck, we'll do our ninety minutes and then we'll be done. We're going to spend the time thinking about something else, anyway. And we are feeling better. And looking better. And it's kind of a nice day today. And we're enjoying the company of the people we run with, who are also looking better and seeming more cheerful. Twelve weeks in, we're actually looking forward to the run. We start thinking about how much further we can run in 90 minutes. We think about how strong we feel, and how much easier it is to run faster. You know, we really feel changed. For the better. Why didn't we do this before?

Most of my readers, I think, are people who ordinarily like hard things having nothing to do with D&D. They choose occupations and past-times that tax their spirit and require lots of time. Things that present lots of insurmountable obstacles that can't be gotten around with a short cut. In fact, I think many of my readers — and I can immediately think of several — have chosen careers and activities that recognise that "short cuts" lead to both injuries and fatalities. So when someone writes, "Here are three simple ways to get your game world started," they immediately think about co-workers and activists who decided they could "simplify" the way they arranged their gear or launched off into whatever.

I have an ex-military friend who received his ticket to work as an electrician and for 20 years worked in a train yard fixing electrical locomotives. From his experience, I can say without doubt that train yards are ridiculously dangerous places, especially at night. I'll give an example, because I can.

An empty flat-car weighs about 80 tons. In a train yard, it's necessary to store empty cars along lines of track, where they'll wait until they're needed for loading. An engine is used to push the car so that it rolls to the end of track — but the engine isn't used to push the car the whole distance. That would be a waste of energy. So the engine gives the flat car a bump, setting it to move about 8-10 miles an hour, then lets it go. The car will roll until it encounters an obstacle ... a line of cars or the end of a track.

At night, slow rolling freight cars are a nightly thing. There's noise all around, from trains moving, machines running, the railroad shop working and so on producing a steady drone in the distance. A rolling flat car in the dark of night makes no sound, comparatively. And because it's flat, it can't be seen against the sky. In fact, it's invisible. 80 tons, 8 miles an hour, invisible, potentially anywhere in the yard at any time. People die. Especially new people. The old hands learn to recognise the very slight sound, the almost imperceptible movement ... and they know never to walk across a track that as if it's empty of cars. EVER.

I think people who work in these kind of environments, or who occupy their free time with similarly dangerous activities, "get" me. They get me perfectly. They understand I'm not trying to simulate real life. They understand I'm trying to present a game structure that requires patience, forethought, internal examination and an inescapable element of risk that must be accepted as unavoidable. They like it. They purposefully move towards activities of that type ... even ones where actual death isn't involved. Ersatz death is enough. And if there is a fail, if something does go wrong, they know enough to admit their fault, confess their fault ... but never to dwell on their fault, because dwelling isn't necessary.

We will make mistakes. We will forget to buy boots, or fail to buy enough food, or overload ourselves to a degree that becomes untenable. But when that happens, we don't blame the rules, we don't look to change the game ... we appreciate that the game has repercussions that produce unexpected effects. Like having to jury rig boots until we can buy them. Or squeezing out another day from the food we have, and searching for alternative sources. Or being unproudly willing to dump expensive crap on the road and leave it behind in order to FIX THE PROBLEM.

Too often, other readers from other expressions of the game rely on fixes that demand changes to the game, rather than changes to themselves. They can't get out and run, and change themselves, because from a young age, they never learned how. They didn't have a father who made them walk miles into the bush in order to fish an obscure river. They didn't have a mother who made them sit through hundreds of hours of old movies until they learned to see the genius in old movies. They never joined a scout troop, or helped build a cabin, or put together a science fair project that took months to plan and build. They didn't learn to build furniture, or use a drill press or a lathe, or set type for printing, or weld metal. They didn't perform their own written work on stage in a city-wide drama competition. They never played on a league sports team, not football or baseball or soccer or hockey. They didn't run track for junior high school. They didn't compete in a chess tournament or a junior high school trivia contest aired on local television. They didn't spend seven days canoeing down a river and sleeping in tents on the shore at night. They didn't learn first how to play cribbage, bridge or poker, and do it often with intransigent, inflexible elders willing to hit impertinent little boys who remarked on "the rules."

I did all these things before I'd ever heard of D&D ... and a lot of other things besides, most of the time because I was forced to. Sometimes because the opportunity was there and it sounded exciting. I think my readers have similar childhoods, which they've brought similarly to D&D.

And I think that many of my D&D playing non-readers haven't.

Friday, May 20, 2022

Expressions

I think it's possible to express the pursuit of D&D, and by extension role-playing games, in four general forms. This is not to suggest that these ways don't possess nuance, a degree of satisfaction or a personal value to the participant. Nor is it meant to say that any single individual must fit into one of these forms. There's room for grey between the forms. That's understood.

Still, there's a benefit in recognising differences. I have an audience, for example. It serves me to understand what comprises that audience, what behaviour they elicit and what things they want. Understanding this ought to enable me to serve them better as a writer. These last few weeks have me thinking at length, "What am I doing here? What am I trying to accomplish?" I'm struggling to find useful and meaningful answers to those questions. Towards that end, I'm pursuing thoughts related to motivation and sustainability.

As I said, four forms:

1. Expression of Energy. D&D is something to do. It isn't necessarily a game, it isn't necessarily what we're going to do on a Saturday night. It's something we do when we feel like doing it, like any other appreciated activity we care to give our energy towards. As such, a minimum set-up is needed. It's best if Bob or Jane or Thomas can open up a few books and run the game easily, without much lead-in time, because we'd just like to get on with it when we feel like playing D&D. In which case, there isn't much need for rules or accounting for things that just don't matter in the short term. The convenience of a module serves, because we can just open one and go. The convenience of pre-made characters, and characters that don't require die rolls to create, also serves since these concessions stream-line the process towards getting play started. Since virtually all the energy we wish to expend is in actually playing the game, and because there is no consistent expectation that we'll play at any particular time — or, potentially, ever again — then most of what's discussed in the books regarding preparation, design, character backgrounds or even a story arc can be discarded.

As such, what appeals is the sense of what we do here and now. Long drawn-out combats soak up time that could be used to move the story-narrative along. The best moments occur when Paul and Dave and Helen are talking together, intermingling their discourse, with a group of NPCs in a fast-paced, excitable manner. Stories that we can fly through, collaboratively, are genius and give a great deal of pleasure. Any part of the game that can be simplified or tossed out to empower this dynamic is preferable and, indeed, obligatory.

2. Expression of Accomplishment. Again, D&D isn't necessarily a game ... but the participants expect a series of building events that promote a sense of purpose that we've invested ourselves into emotionally, in that the time is spent pursuing a final, overarching sense of accomplishment. Play is regular, and the participants are cherished for their commitment, as we intend to play towards an agreed-upon goal. The emotional satisfaction and proud feeling of having done something difficult and worthwhile is the central theme of our gaming. As such, game elements and opportunities that don't directly contribute to the goal at hand can be ditched — should be ditched — for the greater good. Each moment along the way exists in the campaign because it's part of what we've agreed to attain. And therefore, elements of detail, worldbuilding, even choice, can be happily dismissed without feeling that any meaningful part of the activity is lost.

As such, the campaign's appeal can is found in what we're trying to do, both now and in the foreseeable future. Momentum demands that the storyline moves along, that a sufficient amount of the narrative is accomplished each session, so that we feel we're moving steadily towards our goal. Drawn-out combats that must be won in order to set up the next situation are anathema to the activity's agenda. The best moments come when we've done something, when we can get on to the next thing. Any part of the game's rules that can be simplified or tossed out to empower this dynamic is preferable and, indeed, obligatory.

3. Expression of Game. D&D is definitely a game. It functions as an exploratory, adventurous possibility, enabling the players to discover what they can see or do. As such, hex crawling, dungeons for their own sake, personal exploration in character building and design, challenge and inventiveness are all intrinsically part of the experience — which must have, above all, strong elements of amusement and novelty for the participants. Things that are fun, things that are new, things that allow us to run characters we haven't run before, do things we haven't done before, and act our way are highly important to the shared adventure we're undertaking. Aspects of the game that are repetitive, tiresome and not strictly necessary to our fresh and creative agenda can be rejected or — at the bare minimum — grossly simplified so as to allow a quick notation now and again when their inclusion seems moderately important.

As such, participants are welcome to be keen on the game, keen on what the game tries to do and well-versed in the game's concepts and principles without these things challenging the success of game play. No fixed agenda exists as to what we're going to do in any given session — nor is it necessary for sessions to string together with the same characters into campaigns. Drawn-out combats that feel like we've done them before are not wanted, and are better when they can be quickly sorted out or played out in new and exciting ways. The best moments occur when something truly funny and fantastic happens, when someone says or does something so memorable that it becomes a story we can tell ourselves years in the future. Tossing out any part of the game that doesn't contribute to circumstances that empower the dynamic of players interacting with players is preferable and, indeed, obligatory.

4. Expression of Circumstance. D&D is definitely a game. It functions as a rigid ongoing narrative in which individual players strive against limitations to accomplish — and potentially fail at — uncertain goals as a means of self-challenge. It isn't always fun but it is always emotionally engaging, even when everything going on feels extremely awful. Character building is secondary to exploration of "self," the question of what can I invent or what situations can I overcome, through innovation. Amusement and novelty are desireable and appreciated, but less important that proving the party's mettle against all odds. Running the same character in every session, which must necessarily be part of an ongoing campaign, it crucial to appreciation of the game's power to excite the mind. We want to accomplish goals, but they should be our goals; and we will accomplish them in our time, not according to some prefixed agenda or even one at a time. Aspects of the game that are repetitive are what they are, to be accepted as a matter of endurance and pride. Combats must have a strong element of detail, tactical possibility and uncertaintly; this makes drawn-out combats tense and even frightening, especially when entered into with characters whose existence stretches out into years of the player's real-time experience.

As such, participants are committed to the most difficult aspects of the game that are cheerfully dismissed by others: the rigorous keeping of accounts and measures, the unbending rules, the minimalistic structure of playing out a campaign day-by-day with all the attendant difficulties of feeding and housing oneself. These things are embraced because they are difficult, because we feel challenged to see if we can survive in a game world that doesn't make things easy, that demands our full attention, that punishes hard players who forget their boots, who don't bring enough food, who make the wrong move in a combat, who haven't crossed their t's or dotted their i's. Who, in short, can die because they've made one foolish mistake. Any part of the game's rules that can be made more complex, more difficult, more engaging, in order to empower this dynamic, is preferable and, indeed, obligatory.

Conclusion. Asking the question, "which one is best," fails to comprehend the matter at hand. The more useful recognition is that we have groups of people playing four different games ... but we have all of them debating and defending themselves upon one forum. For the most part, the circumstance of one forum leads many of them to believe they're fundamentally all playing the same game, just in four different ways ... but the basics of game theory defines a game according to the strategy, the payoff, the information set being used and the manner in which the outcome is reached. These expressions above are clearly atypical of one another. Commonalities exist, but what's discarded and what's embraced greatly diminishes the possibility of a player who enjoys one of four forms finding any satisfaction from a game played in the other three expressions.

Naturally, there are those who can play each expression comfortably, adjusting their expectations as needed and appreciating what that particular expression offers as an activity. But these people are rare; and must acknowledge that it's a different way of thinking. Moreover, attempting to express one type of game in the presence of a different form creates havoc and discontent among the players. We're either stressing the wrong things, complaining overmuch about what's expected or trying to insert some of the game we prefer into someone else's expression.

Which brings me back to this blog. Like most engaged and committed persons, I have my personal preference; which, logically, I present and discuss in posts here. But since others find this blog by searching "D&D" and not actually the game I play and espouse (one forum, remember), I do much more to turn readers away when I write than entice them. I don't doubt that many of my potential readers have long since given up on the internet because they are looking for my expression, and instead find the other three — which are, without doubt, much more common.

Desirably, when discussing the sort of D&D I play, it's better than I express myself in terms of what payoffs and outcomes I'm aiming to provide, rather than the extremely non-specific, impractical and virtually useless banner of what game edition I play. There is nothing at all in my expression of play that is intrinsically related to AD&D ... which can be easily adapted to the other three expressions. What I've chosen to keep from AD&D are those parts that fit my expression — because they fit my expression, and for no other reason. All other parts of AD&D are useless for me. Which helps explain my tirade recently about how much I've grown to hate talking about D&D. I have. I am sick to death of revisiting any subject material from any edition that matter-of-factly is a useless kitchen sink in my modeled game's structure.

Frustratingly, however, I continue to think I can write the words that will change the world to suit me ... which, obviously, I won't. And so, what am I writing the words for?

Still working on that one.

Thursday, May 19, 2022

A Conclusion to Worldbuilding

Monday, May 16, 2022

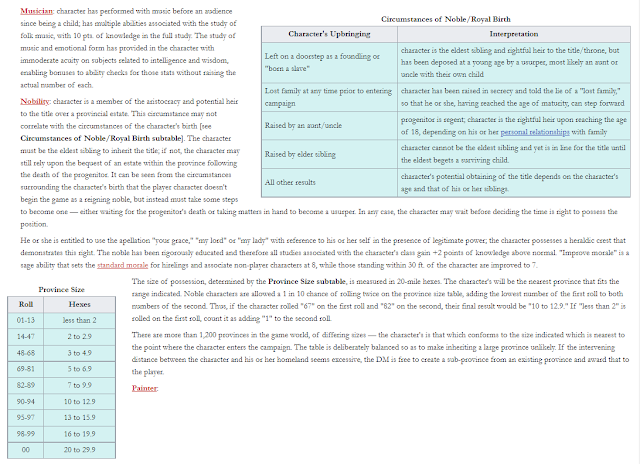

Nobles

Okay, so there's this:

Although on the surface I'm categorically against "balancing" a campaign, as I've discussed before, the above does give me pause. Is it fair to grant one player a lot of money, potential power, the pleasure of being called "your grace" without having done anything to earn it — except being born to the right parents, with land, and even additional knowledge contributed towards sage abilities? Is it not, in fact, a bit much?

On the surface, it appears to be. The chance of becoming a noble is far higher for player characters than the percentage of population would seem to indicate; though of course we're all going to rush to the argument that PCs are "special." My reasons are more that it's interesting to have backgrounds that are both unique and reasonably legitimate in their chance of occurring. It is a mere 1 in 200 chance that any character will be a noble, a member of a royal family or in line for ruling a whole kingdom. That's fairly rare; we don't have to make it 1 in 2000, or 1 in 20,000 just to meet the criteria of demographics.

What interests me is the sort of adventures this builds. Yes, of course there's the long campaign to get the character whose been kept from the title by a usurper, but in the long run that's just one adventure. The harder task is to create adventures for the character after he or she has become the Count of Such-and-Such or the King of So-On-and-So-Forth. Does the character retire, thereafter to adjust laws in the land to suit the player characters? Or can the players invent plausible reasons why the Queen of Country-X needs to slip off and kill a dragon or two? Is it all wars going forward, mixed with the horrors of "accounting" and bitterly adding columns of numbers ... or worse, the palace intrigue of Throne of Games?

[sorry. I know what the title is. Just saying it could have gone either way]

There are sure to be campaigners who hate the idea. "Why can't we all just be ordinary adventurers?", they're sure to argue, wanting nothing more than to play the same old game in the same old way. Thankfully, I'm not bound by this kind of player. I like the opportunities that a different way of seeing the world offers.

And really, the benefits aren't that much. The character starts with some nice money — which won't be all that much once the players participate in a few adventures — which can be shared around if the party has a positive, team-structured attitude. The title is nice, but obviously the party isn't going to use it; if they were asked to do so, that would be quite a joke; and meanwhile, the title's going to get used to help everyone, so it's fine. The hirelings like the character a bit more, so there's less trouble with hirelings; the character will use his or her knowledge to help the party in general; and the +2 bonus for charisma checks will make this character the front guy when dealing with NPCs. That's mostly it ... except for the player actually getting power and being able to use it to have the rest of the party executed.

BUT ... that's only an element of a player-vs.-player campaign. Since I don't allow it, and I'm not going to run your noble character alone, without the party around, I guess you're going to have to see yourself as just another party member. Poor you.

Since the very beginning of my running D&D starting in 1980, that's always been the baseline. We're all friends. We respect each other. We share. I must have been busy running D&D when the toxicity of fuck-you-I-got-mine took over the community. I have experienced it in small packets: game worlds I played in once, and never again — and even, in some cases, for less than an hour before getting up and leaving. The occasional player I've had online who clearly entered the game with Goggles of Selfishness +4. No doubt, one has to be wary. But it is possible to play this game without worrying that making one player a noble will break the party's unity. At least, between me and my friends.

So ... sometimes I don't know what it serves to create rules like the Background Generator in the present climate. I like 'em. The page is 195,446 bytes so far, which would rank 4,744 on the list of longest pages that occurs on Wikipedia. And I still have lots to go.