Thursday, June 30, 2022

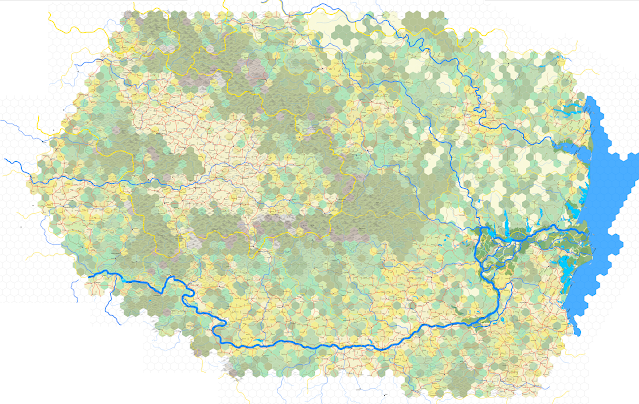

Map, June 30, 2022

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

Let Them Fix It

"A brave man likes the feel of nature on his face, Jack.""Yeah, and a wise man has enough sense to get out of the rain."

There's only so much space in adventure games for wise men. Truth is, unforseen and unpleasant consequences, handled adroitly, result in great triumphs and riches. Don't we know this? Or is it just that we're so certain of our inability to handle things adroitly?

Enough about that. We can take it up in the comments section. Instead, let's examine the three choices presented at the end of the last post. These were not my choices; they were the choices the party settled on:

"The party can simply slink away ... but of course, that's the coward's route and even the most boorish of gamers don't like that label. They can own up ... but, again, Medieval game world, not a liberal mindset among authorities. That's one to hesitate on. Option three? Go back and fix it themselves. Except that now, with evil bad things running all over the neighbourhood, could be there are too many for a party of 1st levels to handle."

I must definitely counsel against 'fessing up. No, no, no. Through humanity's pre-Liberal history, execution was popular because it ensured the criminal would never commit the crime again. There wasn't much worry about punishment as deterrant: no need to deter anyone, we have a sharp axe and we can keep going as long as the executioner's arm doesn't get tired. This mindset remained firmly in place up until someone invented a beheading machine that never got tired, thereafter enabling a resounding experiment in the effectiveness of murder as social reform. Since my world happens long before 1789, let it be understood that the best minds believe firmly that executing the party for "waking up evil" would be authority's first order of business before going off and ridding the evil. After all, we can't have this bunch of boobs waking up some other evil in another place while we're resolving their first blunder.

Personally, I like that my game world's politics and ethics practices a very non-Liberal mindset. This encourages the players to pursue a lack of ethics freely, if they wish ("everyone else is doing it"), while positively forcing them to live in an alien culture. The more alien I can make the game world — and retain it's familiarity — the better. I frankly think it helps to remind people that "complaining about the feels" wasn't always an option on the table. The game as "safe space" is NOT my goal. My goal is the world as fucking decadent unreasoning nightmare hellscape ... mixed with good people who yes, will offer you a cheerful dinner if you're a traveller and you knock politely. Because it's nice.

Option two, then. Slinking away is wholly practical. There's a lot of world, communication is very bad everywhere and starting fresh is always, always, always possible. The 17th century is very local. But ... if you don't stand up to this thing here, you're just going to have to stand up to something else, somewhere else. The reason why we used to use the phrase, "A coward dies a thousand deaths," arises from the coward seeing death around every corner, in every face, behind every door and yes, in a gold ring laying on the floor. Sensible players always recognise that in reality, there's no actual place to run that isn't the same as here. So if we must die, doing it here wears out fewer shoes.

That leaves option three, and the core of this post. The party feels they have to do something, but the problem seems insurmountable. What now?

DMing the problem according to my model means letting the players run their show. If we put the emphasis on the right syllable, then, the title of the post goes ... let THEM do it. This is not the DM's problem. When the players turn to me and ask, "How do we do this?"

— I'm free to answer, "I have no idea. I'm creating a river in Bulgaria. Let me know when you figure it out."

Of course, we're not exempt from describing the world, so we can do that. In the scenario I was running for the players, the killings produced a traditional local response: find out what the evil is, track it down and kill it. Evidence of this movement appeared everywhere. The town called for volunteers, the local nobility was called in, spellcasters interviewed survivors, etcetera. The players were perfectly free to "join up" with the search parties — which they eventually did, temporarily — or sit back and watch the show. Eventually, they decided to leave word of their guilt second hand, so they wouldn't be subject to immediate punishment, telling the Stavangers where to search.

The party headed back to Mimmarudla. They fought some bad guys on the way — "froglings," based on "killer frogs" from the old Monster Manual, but toughed up — and then searched around the original entrance before discovering a second entrance which the froglings had opened. This led them into a secondary dungeon, which they barely survived, finding a passage to the sea at the bottom and escaping. None of them were sailors and they got lost at sea ... but the Stavangers showed up and slaughtered all the inhabitants in the upper dungeon. Then the party were rescued, forgiven for their mistakes and proclaimed heroes.

What was my part, and what was the players' part?

The players chose to send the message. That wasn't me. I gave them someone to send the message to, but it was up to them to come up with the idea. I'd written the idea off by the time they'd made that choice, but I looked at how the Stavanger's would view such a message, told in just that way, and it seemed like a safe bet for the party.

They chose to go back to Mimmarudla. The first entrance was overrun with creatures and no safe, but they made up their mind to search around. So I invented a second entrance because that seemed like something an underground bunch of humanoids would do. Any prairie dog knows one hole isn't enough.

They chose to go into the entrance. I set them up several encounters in a row: giant frogs, stirges and eventually a very strong dog-humanoid that nearly causes a TPK. The party did not turn back. They kept going. When they came to an option of going upwards or downwards — the former requiring that they overcome a wizard locked door, which they could have done with a ring they'd found on the froglings earlier — they chose to go down instead. I had decided before the choice that "down" had a way out, if they were brave enough to go out in a sailing boat they couldn't operate. They were brave enough.

So the party had lots of chances to retreat, and they didn't. They'd made up their own minds and they followed through with their plan. They nearly died but they pushed through. Seems to me that one of their number did die, or got very close, I think it was Embla. They didn't get greedy. They didn't bite off too much. They acted like adventurers. They deserved a reward for that.

Afterwards, one of the players took the position that I'd engineered the whole thing myself. That I'd "manipulated" the party, creating the situation from the beginning so that the players had no choice except to follow the footsteps I put down. It's easy to see things that way. It's easy to perceive, once all is set and done, that the ending had been the most obvious solution all along.

Case in point, Dickens novel A Tale of Two Cities. I assume none of you have read the book, but yes, spoilers follow.

At the end of the book, Charles St. Evremonde, also Charles Darnay, is sentenced to die by guillotine during the post-revolution in France, for the crime of being nobility. At the last moment, a look-alike Englishman by the name of Sydney Carton willingly takes his place, so that Charles can escape and marry Lucie, his love. At first glance, and especially for those who have not read the book or are not good readers, this seems like a cheap plot convenience and is described by many as such. Dickens himself included a passage by Carton in the book itself, in which the resemblance is mocked. Indeed, the sequence is mostly all that anyone remembers of the book, "proving" obviously that Dickens had written himself into a corner that he could only get out from by employing this cheap chicanery.

The book is not about either Darnay or Carton. It's not about the French Revolution or "two cities." Like all great books, it's about the reader ... but it's completely missed in that the reader has no idea that he or she is the subject of every book, just as you, Dear Reader, are the subject of this post.

Throughout A Tale of Two Cities, the storyline investigates the subject material of resurrection ... namely, everyone's. The poor are resurrected by the revolution, Dr. Manette is resurrected from the tomb in which he's lived as a prisoner, the knowledge Manette has, locked in his silenced mind, is resurrected and used as the thing that ultimately sentences Darnay to death, though it's not Darnay that's committed the crime but Darnay's father ... whose actions are resurrected in order to bring about Darnay's sentence. Carton is a drunkard and a person of no worth, whose friends "resurrect" bodies from graves in order to sell them as cadavers. Over and over and over, the book repeatedly addresses the subject of resurrection from every angle, as something which we yearn for but cannot have, or have every reason to fear, because of the consequences of that resurrection happening.

The end is not Carton's demise so that Darnay can live. The end, if one reads the book, is Sidney Carton's resurrection. He climbs the platform and sees himself — for now Carton is Darnay, ready for beheading, and Darnay is Carton,

"... a man winning his way up in that path of life which once was mine. I see him winning it so well, that my name is made illustrious there by the light of his."

Carton had no chance of making something of his life, but now he sees Darnay making something of Carton's life, and it fills Carton with joy. He looks around at the horror, the cruelty, the barbarism,

"... The Vengeance, the Juryman, the Judge, long ranks of new oppressors who have risen on the destruction of the old, perishing by this retributive instrument, before it shall cease out of its present use. I see a beautiful city and a brilliant people rising from this abyss, and, in their struggles to be truly free, in their triumphs and defeats, through long years to come, I see the evil of this time and of the previous time of which this is the natural birth, gradually making expiation for itself and wearing out."

Resurrection. He sees resurrection. His resurrection. And yours.

It should be noticed that I don't quote the famous last line of the novel, because that last line is always quoted out of context. There are two pages that build to that last line, which explain that last line ... but readers so often skim and skip, and fail to see all there is to see.

I apologise for the departure, but I wish to convey the manner in which humans "miss" things, including their own actions. D&D is thick with it. The DM has such a remarkable amount of power, that players have a tendency to perceive that everything bad that happens must be the fault of the DM ... and that therefore, everything good that happens must also be the DM's doing. However much we strive to wash ourselves out of the framework, the players are ready to put us back there because all too often they are unready to see themselves as capable and able directors of the game.

Players must be willing to put themselves "out there," to step up to the plate and swing. And to make that work, the DM must throw good balls as well as bad ... every one designed to be a strike, but every one able to be a home run.

The ball before it leaves the pitcher's hand has every nuance of being an "unpleasant" possibility ... but we don't know if it is or not for SURE until the player swings.

Like Carton, the player has to look past the two-dimensional construction of the situation appearing so "obvious" and recognising that beneath appearances, there are chances and opportunities, ways of looking at things, that surpass the common constructions of human achievement.

The simplicity of the dungeon-structured game has blinded players. It's taught them that the procedure is exactly that which is expected. But once we separate ourselves from that structure, once we let the players choose their own way of handling problems, the bets are off. Hitting the ball is less about "knowing how" and more about gumption and resolve.

Sadly, even when a player has it, they've been trained to suppose it must have been me.

Players do shake that off, once they've played enough D&D. Once they've had a chance to make their own decisions. And once they have ... oh, it's not possible to go back. No. No, it's really not.

Monday, June 27, 2022

Have Them Set Something in Motion

1. the DM describes a scene.2. the players express their actions.3. the DM describes the effects of those actions.

Sunday, June 26, 2022

Have Them Find Something

Saturday, June 25, 2022

Personality Building

Monday, June 20, 2022

1% Inspiration

The perspiration is yet to start:

The sage abilities discussed on this page, not included in the teaser above, finally establish once and for all my method for characters making magic items in the game. It's not merely an issue of spending a lot of money and buying the place where the fabrication takes place, but with deliberately seeking out certain studies early in the game that permits item creation by potentially 7th or 8th level — although to do so this early would require more than one character to likewise make plans.

I've said before that the goal with creating magic items and invoking similar profound magical effects is not to throw thousands of gold pieces at the problem and then roll dice, but to spend much time, so that only so many items can be created before the character becomes too old to adventure. It should be supposed that yes, a player character CAN make a vorpal blade or a +5 holy sword themselves ... but that the time scale on these items should be ten years.

This includes an understanding that such items are so rare that no, the player cannot go out and adventure for such things in the space of a few months. Ten years of game time describes how long a character ought to adventure in order to achieve a level to where they could conceivably take a holy avenger out of the hands of the 22nd level paladin wielding it. It's not my feeling that a weapon of this kind should be found stuck in a rock at the end of a platform in a deep dungeon ... unless the nature fo the rock, the dungeon and the time it took to get here made the character pay the necessary cost to even see the thing. Just cause we're here, and can touch it, doesn't mean the rock will let it go.

Anyway. There's no rush to actually detail the sage abilities; I haven't any characters yet who have chosen these paths. Study "flowers & sprigs"? Who knew?

It helps, however, to know they're there, and how the path to reach them works.

Sunday, June 19, 2022

Players who Have Played Before

I have to be careful with this last post on the subject of bringing in new players — and here I'm speaking of players who are not new to the game, but are new to my campaign. Having discussed the subject on numerous occasions in the past, I see little value in rehashing old wounds and mistakes made. People make a mess of relationships for all kinds of reasons ... and more often than not, they don't get resolved because one or both parties feels a crushing load of shame, and not because there are irreconcialable differences.

Recently, I met a former player who left my campaign in and around 2012, largely because he was in a difficult place in his life and chose to abandon other activities in the pursuit of recreational drugs. His leaving the campaign was equitable, but of course not well-respected. He's been clean for years and years now ... and in this post-covid time, I asked if he would be interested in rejoining my campaign. His face lit up and he expressed a strong desire to do so; and later I heard through a third party that he'd wanted to rejoin the campaign for five or six years, but simply couldn't face me to ask. I saved his face by asking him.

This is how it goes with people. Harsh words get spoken, the argument gets forgotten but the feelings do not. It's one of the reasons I'm trying to change my ways and put an end to my ranting nature. It's not that I've changed my mind on the fallacies of other DMs or that I suddenly respect or choose to tolerate what I consider wrongness in managing players or the game itself ... only that people tend to remember the hurt and not the argument I've made. This has taken a long time for me to accept; and most people, I know, would feel too ashamed to admit it.

Anyway. I really should stress that for the most part, I do very well with new players who have plenty of experience with D&D. Most are tired of cookie-cutter games and want something on a deeper level, as several of my online players will attest. There's little to be said about people like this because they are so easy to run and get along with that I look forward to their involvement. I don't have to overly explain the character generation process, I can make a few quick points about rule changes, negotiation of said rule changes go swimmingly and overall it's less work to initiate a good experienced player from another campaign than it is one who has never played before.

The trick is, of course, recognising one of these good-and-experienced players from those who are intrinsically toxic. A toxic player is also very good at playing; they are also very good at adopting and understanding new rules, and very often are very good at negotiating those rules to understand their stance. Toxic and non-toxic players alike make good role-players; and they are often both pleasant and cheerful to associate with. It's the samenesses that make it difficult to deal with toxic players ... because in the beginning, we're never sure that's what we have.

Fundamentally, the toxicity derives from two positions on the game that underlie the player's intentions: (a) winning and (b) self-aggrandisement. In all fairness, these are the same problems that affect persons in business, in sports, in politics and in relationships. The characteristics need not be overly pronounced like a made-for-netflix movie. The need to "win" a situation, or "serve myself," need not manifest as a slavering workaholic fuck-you-I-got-mine perspective that is coldly evident on first glance. It is most likely very subtle.

The need to win is more often a need not-to-lose, and more specifically a need not to fail. Failing is the criminality that produces many toxic players ... not just the need not to make mistakes or approach the game with a "failure-is-not-an-option" attitude, but the need not to look like I've failed, or admit that I've failed. These last two, and the inherent shame that saturates both, gets into the blood of a campaign and begins to taint everything. Especially when "winning" becomes the equivalent of not putting one's self into a position where losing is possible.

This explains players who won't invest, who won't take risks, who won't calculate the odds, roll the dice and accept a negative result, on principle. It's not that a negative result, in principle, is something that can't be sustained, but that there's a shame in having to accept that "I made the decision that put me in a place where a negative result was possible." This belief in self-imposed shame is taught at a young age by fathers, mothers and coaches the world over. I quote,

"The bizarre thing is, I did it for my old man. I tortured this poor kid, because I wanted him to think that I was cool. He's always going off about, you know when he was in school, and the wild things he used to do. And I got the feeling that he was disappointed that I never cut loose on anyone, right? So, I'm sitting in a locker room, and I'm taping up my knee ... and Larry's undressing a couple lockers down from me; and ... and he's kind of skinny. Weak. And I started thinking about my father, and his attitude about weakness. And the next thing I knew, I jumped on top of him and I started wailing on him. And my friends, they just laughed and cheered me on. And afterwards, when I was sitting in Vern's office, all I could think about was Larry's father. And Larry having to go home, and ... and explain what happened to him. And ... the humiliation ... the fucking humiliation he must have felt. It must have been unreal. Huh, how do you apologise for something like that? There's no way. It's all because of me and my old man. God I fucking hate him. He's like ... he's like this mindless machine that I can't even relate to anymore. 'ANDREW! YOU'VE GOT TO BE NUMBER ONE! I won't tolerate any losers in this family! Your intensity is for shit. WIN! WIN! WIN!' You son-of-a-bitch."

— The Breakfast Club

Obviously, it's not as clear as that. Not usually. It manifests in the player being so cautious that other players are left in the lurch, unprotected. Or the player deliberately building the character in a deeply munchkinian way, or thirsting after more and more magical items, or anything that will serve as a bulwark between success and losing ... because they cannot lose. The feeling they have of leaving a campaign where they've lost is emotionally crippling — and reminds the player that this is NOT why they play D&D. It's bad enough that this failure and losing are part of real life; the craving to escape that real life shame by rushing into D&D, or any escapist activity that assures success, absolutely, is their fundamental reason for being here.

The story is fun, the characterisation and situations are fun, the loot and the power building is fun, the triumph is fun ... but anything that's a part of the game that the player cannot utterly control on every level is anathema to the dogma. Math is an excuse; the real reason why encumbrance, tracking food, the number of spells one can cast in a day, having to live with less than ideal hit points and so on is so hateful is because they're all a reminder that the character is limited, and limited equals weak. Weakness is the precursor to failure; no matter how we cut it, "Sooner or later the place where I am weak will lead to my failing, and I just fucking cannot deal with any more failing, especially in an activity I do for fun."

In my book How to Run, I talked about the accumulated pattern recognition that's gained from running D&D over a period of years. One of those patterns I've been made to recognise are the tunes and tones that enter the player's diction as the game is played out. Players learn a semantic and conceptual way of understanding what the game is about, for them, which when obtained is virtually impossible to shift or change. The desires a player expresses in the first few rolls of creating their character; the way they express what they think the party should do; the hesitation they show when meeting a particular danger; the manner in which they physically have their characters approach that danger; the way they withhold powers they possess, "saving them for later," which they perceive is good play but is often evidence of not wanting to let go of something held too tightly, "in case." Altogether, it expresses a doubt on the player's part that things will work out, or that they can think their way out of the problem when the need arises. They don't believe they will; or, in the very least, there's a strong feeling that they might not. And they are simply not willing to take the risk that they might have used a power now, when they'll so desperately need that power later.

This approach of anti-failure by excessive conservation of power seems like an example of "good play." It's very often defended that way. A long-time savvy player will have accumulated many examples of evidence that supports this approach, ingraining it further into the player's consciousness as "the right way to play." It is, at best, "a" way to play. Unfortunately, it's a heuristically oriented approach, where the player has learned this habit entirely for themselves, and not within a social context. Socially, the player's failure is less intrinsically important than the party's failure ... but the player who must win is universally incapable of making this distinction. "The risked shame isn't the party's shame; it's MY shame. And as long as it's mine, I'll decide for myself how much of it I want to endure."

Taking us to the place of self-aggrandisement. Let me stress here. This isn't about being selfish. Nor is it necessarily about pounding one's chest and promoting oneself as being powerful or important ... though yes, let's admit it, that's been a core-rhetoric in D&D since it's beginning. We have many famous quotes from Gygax, Mentzer and others that are boasting, strutting and thoroughly toxic. The meme of gloating player goes well back before Knights of the Dinner Table and the earlier Fineous Fingers. Oftentimes, old schoolers achieved a certain glee in depictions of this sort.

Just as "to win" means to not lose, being important is served by not being overlooked. However popular RPGs and D&D in particular may become, it's still an activity enjoyed by those who are educated and possessed of a heightened imagination. Such persons nearly always end up spending a lot of time alone, in part because they did the homework they were given, in part because they retreat to imaginative activity as a means of freedom in an environment that's not pretty. Learning how to manage ourselves and the various details in the world have much to do with an individual's life trajectory — and a long-time situation of diligently doing school work and being occupied with one's own thoughts rarely leads to a path of "being cool" and having popularity.

Those who have a supportive family are comfortable with their level of importance. Those who receive accolades for their schoolwork, or who have even minor athletic gifts or an ability to participate as a team member gain early recognition for their existential importance in a group. If they're among others and an hour goes by without their gaining any special attention, they're fine with it. They've learned, either subconsciously or through the point being highlighted by some personal event, that everyone gets their kick at the cat, eventually ... and that ultimately everyone deserves that kick.

For some, however, cat-kicking possesses something of a dearth in their existence. They're fairly convinced — AGAIN, either subconsciously or through the point being highlighted — that they haven't had their share of attention. And it's very, very hard for them to sit among a group of people and not be recognised a requisite number of times ... that requisite being decided in their minds, and not according to some other, more socially agreed-upon measure.

In it's worst form, this manifests as the grabbing character who must have the best object at the table, for being the strongest and having the best is surely a way of getting attention. Toxically, it also manifests as a need to push others down, since the importance of others is a challenge to the player's importance. Much of this stems from a certainty that there's only so much attention to go around, that it's in short supply or that it must at least be cornered to the greatest degree possible. Time, after all, is a limited commodity; therefore it follows that attention must be also. "And anyone else getting attention robs me of mine."

But ... these monsters are so obviously horrific that types like this never get invited to my house, much less be given an opportunity to play in my world. I've had a few of them turn up online; but they're easy to identify and dispense. The more obscure variant of the species is the player who seems perfectly normal in nearly every aspect, except that — often to a very slight degree — they have trouble keeping themselves occupied.

The rest of this sentiment can be immediately recognised by any DM out there. These are players who need a lot of handling. Less needful of gaining importance from the rest of the party, they zero in on what the DM can give. Being imaginative, they're full of ideas of things they want to do; but they usually lack some skill in getting anyone else interested. Usually, it's because the "things" are impractical, too personal or ultimately not very lucrative. Sometimes, the player will urge the DM to step in and ensure their idea becomes the game's direction — through wheedling or merely by never dropping the subject, ever.

It's an Amphipolean problem, which can only resound with those studying Greek history. The party get tired of hearing it, the DM gets tired, the issue never gets dropped ... and increasingly the attention-seeking player chooses it as the hill to die on, the evidence that "No one ever wants to do the thing I want to do." Sooner or later the thing will come to a head; and the worst of it is that in not giving the player their kick at the cat, denying the player further participation in the campaign feels like kicking a dog.

[Sorry. From the moment I wrote about kicking the cat I knew the other metaphor had to find a place]

There's something undeniably hateful about pushing a fairly benign, often quiet, often socially paralysed individual out of a game ... so hateful that a DM — certainly me — will endure the situation for years if it means not having to address the matter. In reality, the party begins to ignore the player, I begin to ignore the player, all because the player can only see the game from their personal, self-identified point of view. And being ignored is the thing that player least wants to experience. The situation is awful. No question about it.

Unfortunately, social situations have their rules. Participating in a social situation requires that the individual be conscious of their personal need to be socialised. They must gain a comprehension of other people's needs, they must learn to view themselves as a part of a group and not an individual within a group; they must reflect upon how their language and their choice of subject-matter affects other people. They must learn to give life to their words so that the words deserve attention, not the speaker.

These are skills we all must learn. No one learns them perfectly. Many reach a certain point and quit learning. I personally wish to keep working on my socialisation for the rest of my life.

Concluding this series of posts, I'll end by saying that the goal of introducing a new character is to ensure the machine, the game, keeps running fluidly. Whether the new player is wholly new to the game, or any RPG, or comes from other games to play yours, the DM should strive to keep the cogs and rods lubricated and smooth-running. Any bit of grit, that occurs for any reason, is contrary to the manifest importance of a well-run, humming and exciting game.

Understanding that "grit" is defined according to what sort of game you're running. In most games that others play, I would definitely be a very large bag of sand thrown into the gears.

Best that I don't play, then.

Friday, June 17, 2022

Bringing You In

As I said with this post, at the beginning of my D&D playing I was told to "watch and learn" ... which I did. My first action, taken in haste and without understanding the consequence, got me turned into stone; whereupon I had little choice but to watch and learn.

The lesson here is that it didn't matter than my first experience was "easy" or not. What mattered was that the party didn't overly mock me for being so stupid or in any way make me feel unworthy as a player. Instead, as soon as they could, they got me turned back to flesh. This is what matters. As a player in this game, bad things happen. It isn't the bad things themselves that turn players off, it's the way that other players, and DMs, respond in those moments.

Whatever I felt about those guys later — I played with them for 18 months before deciding their goals were fatuous and limited — they brought me in, adopted me as a player, let be become one of their number and didn't hold it against me when I stopped playing. By the time I quit, I had three other regular games to play in and my own to run, all of which gave me a lot of experience in a short time.

Once a new player in my campaign gets to where the character is sorted, we can play. The situation is briefly explained and the new player is encouraged to ask questions. Usually, off balance, they have none to ask and we get into it.

Let's say we're in a dungeon and you, Dear Reader, have just joined the campaign. Now how does that work? The party is fifty feet underground and they've slogged through a hundred vermin to get here, and now you saunter as if you were looking for the washroom and you've ended up here. I know that other parties make a big deal of such meetings, trying to justify this strange happenstance, but I prefer to wrap it up with something simple. I've introduced hundreds of characters to games and I'm rather bored with the fifteen-minute "getting to know you" scene. Rather, I'll say something like, "This is Horace, the fellow you met at the tavern in Ipswich three days ago; remember suggesting that he ought to come along? Well, he's been about fifty yards behind you this whole time, getting over his nerve at the sound of battle and so on ... but here he is, ready to fight. Aren't you Horace?"

You say yes and there we are. The players ask about your equipment and if you're short a helmet or a weapon, they'll give you one. "Uh, I had this extra +1 hand axe I'm not using right now; can you use a hand axe?" "You've got leather armour? I've a suit of +1 studded on my horse; if we get a chance, I'll give it to you." This sort of thing.

I'll ask the party, "What next?"

And they'll say, "We're going through the door." They outline where they're going to stand and who will do the actual opening and I'll ask, "Where should Horace stand?" This is me ensuring you're not forgotten; I know you, as a new player, haven't any idea what this "where are we going to stand" thing is all about, so I'm there for you. The party will tell you to stand here, draw your bow, point it at the door. If anything comes in, shoot." I move your image to a place on the map you can see, on a monitor screen. That's you. You can see how you relate to everyone else.

That'll sound reasonable to you, there's no reason not to trust this party, they've been friendly so far ... so you say, "Sure." The door opens and 20 bats fly through and into the room. You blurt out, "I shoot at them!" and I say, "no problem. But first, we have to see if you're surprised. You didn't expect bats, did you? Roll a d6."

You're rolling the d6 for the whole party, but you don't know that. I can get anyone to roll that d6, and the rest of the party knows this, but I'm picking you because you're new and I want you to feel involved. You roll a one and the party groans ... and maybe you clam up in confusion or maybe you ask, "What? What happened?"

And I'll say, "You rolled bad and the party is surprised. It means the bats get to attack first."

Whereupon if you're chatty you'll say, "Gee, I'm sorry." Keeping in mind that most new players don't say that or anything, they just feel real bad they've screwed up — without even knowing why or how they've screwed up.

"Don't worry about it," I'll tell you. "You were rolling to see if the party was surprised is all; it happens. These guys are tough. You'll be fine." I start filling the monitor screen with bats and as they pop into existence, there looks like way too many bats ... and you start to feel uncomfortable as more and more appear. You feel a bit of a blood rush and so do the others. Now I'm slating how many bats are attacking and who gets how many attacks against them personally. This is done in the open, no DM screen. I run through this process with about 20 seconds per person or less; we'll say two bats attack you and I'll ask your armour class. Not because I don't already know your armour class, we sorted that out just half an hour or less ago, but I want you to look up your armour class so you can see where it is and remember it. You tell me the number and I roll, saying I hit you once for 1 point of damage (they're only bats). "Remove it temporarily from your hit points," I say, "While keeping your maximum written on the page." If necessary, the player on one side of you will show you what I mean ... or maybe you just saw her cross out her own present hit points because she was hit for 2 damage.

"Okay, party's round," I'll say. I go around the table, one at a time. No one rolls a die or makes a statement about what they're doing until it's their turn. I point at Jimmy and he picks up a die and says, "I attack," without needing to say with what weapon; essentially, his main one, the one he nearly always uses. He'll only specify a weapon if its something else.

Although he has the die in his hand, and he's shaking his hand, he won't let that die go until I say, "Okay, roll." If he rolls before I say, the number doesn't count. But I don't hesitate. The second he says that he attacks I tell him to roll, because I want the combat to go fast, fast, fast. Player, player, player, 20, 40 seconds a player. While Jimmy's die bounces on the table I'll say, "Allie, you're on deck."

What does that mean? It means, Allie, get your shit together, get ready to tell me what you're doing when I call your name or point at you. Hearing me say that Allie is on deck shakes her out of her lethargy as she watches Jimmy's die bounce — she wants to know that result as much as anyone, but I need her focused on the next thing, too. Jimmy calls out the number of his die, a "7." I don't like Jimmy to withhold the die and say, "I missed," because in reality, I've learned that many times the player is wrong about that. Jimmy doesn't know what the armour class of the bats is; I do. I also know Jimmy's level and his THAC0, so I can say absolutely that a "7" hits, because these are big, slow-moving bats that have been woken up out of their sleep and in a cold room. Jimmy is happy and rolls damage. "Allie, you're up," I say. "Horace, you're on deck."

Now, maybe you say "What does that mean," but probably you've heard of baseball and — having seen Allie's turn come up — you can figure it out. Maybe you ask, "What do I do?" Chances are I won't answer that; I'm listening to Allie tell me what she's doing ... but here I can count on a player to say something like, "Get ready to attack." If you have dice you've bought, he or she might pick out the d20 for you. Allie wants to use a gadfly cantrip to attack a bat, which works because the casting time is so short a bat doesn't have time to spoil the magic; not that you, a noob, understand this. Nor is there time to explain it; you're reaching for your d20, you hear the word "cantrip," which is utterly meaningless to you. I say "go ahead" to Allie, who hasn't technically thrown the cantrip, and she instantly says, "I do," which means she's now thrown the cantrip, and before I take a hit point from the bat I turn to you and say, "You have your bow out. You need a different weapon to attack the bats." Then I turn back to Allie and say, "Your cantrip killed the bat." Poof, the bat disappears from the screen. "Anything else you want to do with your move?" She tells me, I move her little image on the monitor screen and now I'm turning to you and asking what weapon you're using to attack a bat. You say, maybe a little confusedly, and I tell you to roll your d20, and since it's already in your hand, you know it's the one to roll. So you do. And I call out, "Taber, you're on deck," as your die bounces on the table.

See, now? You're in this. You feel the speed as I move around the table, you feel the experience I have in managing multiple details at one time, the sense of things moving around you, the image of the bats popping off the screen ... this gives you the feeling of being in a fight, of standing with others, of not having time to chat or ask questions. No one else does, not now, because I'll shut them down if they choose this moment to talk about anything except the combat going on, in the order their names are called. You don't feel "new." Just like that, as puzzled as you are by all the terms and choices being made, you feel like a member of the party. And as you learn the terms, hearing them used again and again, it all becomes comfortably familiar.

But suppose this is not how you're introduced to the campaign. Suppose the party's still in Ipswich when you join the game. "This is Horace," I say; "He's been listening to your conversation and you've gotten to know him." Again, we skip over the introductions. The party is talking about what they want to do next.

Allie says they ought to hurry back to Cirencester and fetch the book they need before heading north. Taber worries that the wizard won't part with the book unless something is done about the situation with the wizard's daughter. "We ought to fetch her back from St. Albans first," he says.

Jimmy says that before they do anything, cash is getting low. "There's a dungeon right there in Thetford Forest," he says. "We know where it is. Why don't we hit it now?"

You ask, "What's a dungeon?" and I say, "It's an underground set of catacombs where monsters live." And Jimmy instantly adds, "With lots of treasure."

You're really a noob so you ask, "Treasure?" So I say, "Yes, loot. Plunder. Gold coins, jewellery, magical items ... fun stuff. You need 2,251 experience to reach next level. A dungeon is a way to get it."

"Oh," you say, not really understanding, but getting a sense that it's a place to go. I quickly explain how the wizard's daughter has run away from him to marry her lover, but he's abandoned her and now she's sheltering in St. Albans and is afraid to go home. The party was hired to find her in Ipswich, and they've just learned she was jilted here and that she's left for St. Albans to hide from her father with a cousin.

Allie says, "First, we go tell the wizard where his daughter is; he gives us the book, goes and fetches her and then we can hit the dungeon before going north."

Taber says, "We get the daughter first, take her back to the wizard, exchange her for the book and hit the dungeon before going north."

Jimmy says, "We hit the dungeon first, and then we can figure out what to do after that. If we die in the dungeon we've saved ourselves some trouble." He laughs. The others laugh.

You ask, "Die?"

I say, "You lose all your hit points and your character is dead. But that's not likely with this crew. They'll have your back."

And Jimmy tells you, "Not to worry, I'm just kidding. What do you think of my plan?"

Because they've been trained to think as a group, they want your opinion. For one thing, you're the deciding vote. It doesn't matter to them that you're new; in reality, one choice is as good as another, and once they've made up their minds, they'll move on. This whole resentment thing you hear about with selfish people who stew that they didn't get their way? They got turfed out the door months, years, decades ago. Besides, you've never played before. You have no idea that people actually get upset when they don't get their way. It all sounds interesting to you. So when you say, "I think we should get the girl," Taber cheers and the others go, "Okay, fine. But we're definitely checking out the dungeon after."

Everyone says "agreed" and as the party heads for St. Albans, you feel like YOUR voice matters to these people. That you've made the decision for them where to go. That it's okay to speak up, even if you are a johnny-come-lately. That taking part is something that's acknowledged as a good thing ... and at the same time, there's a feeling that no one's trying to freak you out about what might happen.

I really hate negativity in a campaign. I dislike unneeded mind games, or people deliberately making up stuff to get a reaction from others. And woe betide anyone who catcalls or shows the slightest glee at another player's misfortune. You won't believe how fast I'll come down on someone who does that. Everyone gets my attention and everyone is subject to misfortune if they try to get my attention for them personally when I'm giving it to someone else. Everyone waits their turn. When the party wants to hash something out, I shut up. I wait until information is needed, but I don't wade in and tell anyone what to do. I don't care if the party goes to St. Albans or Cirencester or Thetford Forest. It's all the same world, all the same campaign to me.

No one is "special" ... because everyone is treated with grace, consideration and according to their needs at a given time. Players who come in, new players especially, see and recognise this almost instantly, making the game easy to run.

Savvy players, on the other hand ... those who have learned a lot of bad habits from other campaigns ... they can be a fucking pain in the ass.

I'll talk about them next.