While no doubt it's useful to have me interpret micro-geographical features into adventure possibilities, this isn't the only goal at hand. The subtext underlying every adventure must be more than, "Keen, we fought off river pirates and visited the Well of Lered." Tourism is nice and fun, but of greater import is to give the players a sense of

mastery over their environment ... the notion that upon entering a large, impressive city, the character thinks, "One day, I'm going to own this pile of rocks," rather than "Ooh, aah ... big!"

Not that I haven't made the point before, but ... requiring players to start with first level characters, even when everyone else is 9th level, accords a tangible sense of accumulated mastery obtained through effort given. Players who start as a bunch of drifters hoping to accumulate enough coin to get themselves good armour are building memories for the day when they buy two hundred suits for their honour guard before marching their armies into a neighbouring kingdom. There was a time, they'll always remember, when an ogre was scary ... and when the day comes to fight the beholder, they'll cheer themselves forward by saying something like, "Remember when we couldn't handle an ogre? Come on, guys ... we've got this."

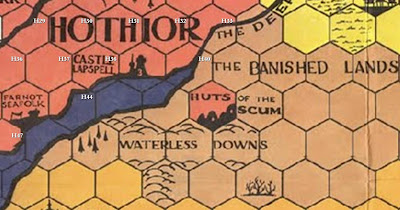

I bring this up because the kingdom of Hothior isn't anything like Mivior. Here. Have a look:

If

Mivior is an enclosed fortress facing the sea, Hothior is a natural cultural and economic powerhouse. Observe it's location within

the greater continent. It straddles the outflow of three significant rivers: The Deep, the Flood Water and The Ebbing ... each of which grants Hothior access to the interior far beyond the lesser benefits accorded to Addat in the last post, which is near the mouth of The River Sullen. Ignoring the needs of the game Divine Right, the origin of the map, a D&D version of Hothior would be the world's marketplace, similar to the geographical benefits of the Netherlands of Earth.

Presumably, there's another group of lands across The Sea of Drowning Men, from which arrives great ships docking at the mighty ports of Lork and Lapspell. The river basins would have rich soils, particularly the Flood Water, while raw materials from Immer, foodstuffs from Muetar and riches from Pon would find their way down river to be sold in Hothior markets to the rest of the world.

For traditional players and DMs, looking for "recognisable" D&D, this is a setting fraught with confusion and difficulties. Like those DMs who eschew any adventures in towns — unless its a jaunt around the local dungeon-like sewers — Hothior's law & order, heavily taxed and organized setting offers very little. It's too big to plunder; there are too many eyes on the players actions; one little mistake and it's guards chasing us through the streets and prison to follow. Players just want to get out, get back to the wilderness, where an adventurer can slaughter a goblin village with no one being the wiser.

Without a sense for the devious or an understanding of how factions operate, it's very difficult for a DM to run "Civilisation." The players cannot just take out their weapons and start casting spells in town, because "town" is populated by three or four thousand citizens at least ... a few more than an ordinary dungeon with 60 monsters carefully catalogued into bite-sized pieces. If the town comes rushing into the street, the players are perceived to be, well, fucked.

Yet we blithely watch film after film of good guys and bad guys fighting running battles through streets, where the police are competent only at piling their cars upon one another while masterful artists like Jason Bourne and James Bond zip, leap, dive and dodge their way out of trouble with ease. Is it just that there are skills that ought to be in place? Or is it that DMs can't visualise the layout of a town sufficiently to let the players conveniently slip out of sight quickly enough to let a passel of guards run by?

And if the danger in town is that much greater, shouldn't the rewards be that much greater as well? After all, as I explained above, where Hothior is concerned, the money is here. As with Antwerp, Cologne and Amsterdam, half the money in the world is either flowing into Hothior or out of it. Surely the players ought to find a way to dip their hand in the pouring river of money and dredge out a worthy bucket or two.

But no. That's not the players' experience. So they anxiously buy a few things they can only get here and vamoose out of town as if chased by their bootstraps. And DMs sigh relief as they do, so we can get back to good ol' traditional D&D, the way it was meant to be run — at least, according to a bunch of dead guys whose familiarity with the modern world has already shrunk to nothing in the rear view window.

We're not here for this, though; we're here for me to deconstruct the region and explain how topography and other features contribute to game play. I'll get on with that.

Like other kingdoms, Hothior has its own troubles. Mivior on the west is an occasional interloper into the Bad Axe forest, as shipbuilding there has a neverending demand for wood — wood that Hothior would prefer to keep for itself, to support boat and shipbuilding in Port Lork. Despite the mountains in the northwest, trolls have more than once circumvented the mountains and laid siege to Tadafat, cutting off trade along the Ebbing and burning surrounding fields. Much of Hothior's northern boundary is unsecured, in part because too much public spending to defend against the barbarians there is money not spent to protect against the large, dangerous kingdom of Muetar to the east. Camel raids from Shucassam wade across the Deep during the late summer season and create other headaches for the lands east of Lapspell. And, of course, there are The Banished Lands.

First, a word about these. There are no Earthly examples of an inlet or estuary bay with this sort of climate on this bank and that sort of climate on that bank. The St. Lawrence River is the largest estuary in the world ... and yet both climate and topography are indistiguishable. The same can be said for the Rio de la Plata in South America, the Gulf of Ob in Siberia and Meghna estuary below the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers. So, nonsensical. But I know readers will only shrug their shoulders and argue that something huge and magical happened here, that blasted the land's soil and made it impractical for Hothior to simply occupy both sides of the river and extend its boundaries logically to Shucassam. As the map says, however, those downs are

waterless.

So, instead, let's talk about the "Huts of the Scum." It's a deliciously suggestive name for groups of weak mercenaries available in Divine Right's game play. They're worth talking about here because they represent a non-structured populated entity outside the rule of law and kingdom. Traditionally, DMs would make the place into a "black market" bazaar, where players can buy "anything" — as reflected in the endless cliched existence of Mos Eisley, Bartertown or any other fictional out of the way place. Naturally, merchants love hauling their stuff 20 or 30 miles away from a river into the middle of a desert, to sell in an atmosphere of arbitrary law and zero meaningful justice, because obviously the tyrannical "might is right" leader of the Scum would never randomly seize all our goods and then bury us in the desert, right?

This is definitely a lot better than selling these same goods in a town right on the water just over there, where there are thousands of customers, a guild to protect our goods and profits, and the ability to pass along taxes to the suckers, er, the good people of Hothior. Yeah. That's how things work.

Turning the huts into a desert bazaar is weaksauce. What about scores of scattered villages of refugees, eeking out an existence of desperation and humiliation ... which actually occurs in places like Afghanistan, Mali, Iraq and Palestine. And how do the able youth free themselves from those places? They willingly join as fanatics for the cause of some would-be dictator, ready to sacrifice them as ill-bred cannon-fodder.

Players, however, might recognize a better, higher purpose. They might investigate water sources, cutting their way into a few underdark places, recognising that if the "Scum" can be set free, and if the Banished Lands can be made healthy, this is a ready starting place for a client-kingdom of either Hothior or Shucassam. A buffer state, even, if it's able to hold its own through the plucky ability of a group of 14th level player characters.

This comes back to an earlier point: how can the players make themselves useful? The Huts of the Scum needn't be just another kiosk for players to buy shit. It can be a piece of ground the players acquire and place under their jurisdiction; a place from which to build; or at least a place where they can return to again and again, as a friendly place that remembers what the players have done and is always ready to help.

In the same manner, traditional D&D would demand that the Bad Axe forest is full of dark evilness, and most likely some forboding, evil-based fortification the players can journey to as a single-shot adventure ... whereupon, the Bad Axe forest is totally forgotten, having nothing else to offer.

In truth, as I've said, Hothior greatly depends on the forest for its industry; it's control over the forest is vital to its military and naval interests. Timber is a valuable commercial product — yet looking at a game's setting this way is treated as "anti-fantasy" and therefore anti-player. I disagree.

Each hex of the Bad Axe carries its own personality. H27, adjacent to Port Lork, is the primary source of timber. H34, accessible from the sea, makes another convenient source. Even better, H34 is split in two by an inlet ... and we may assume a small stream, not shown on the map, wending its way up through H26, H18 and H09, to the Hothior controlled mountainous hexes H01 and H02. The east bank of this wild course is safely Hothiorian ... but the west side is full of Miviorian timber poachers, criminals escaping both Miviorian and Hothorian justice, plus the occasional wandering troop from Trollwood or the Shaker Mts. The west side of H34 and all of H26, most easily accessed from Mivior, are the most likely places to meet bandits and poachers.

H18 and H10 are occasionally logged, especially for the largest trees, since most of those are missing from the forest closer to Port Lork. No doubt, the army of Hothior occasionally plunges into H17 and H09 to resecure these parts ... but perhaps no more often than every five years or so. In that time, a kobald village may have been founded, or a nest of vermin has accumulated; or even some hideous beast and torn apart a section and created an immense lair for itself. And of course there may be a dungeon of some kind on the lower slopes of the Shaker Mts., anywhere in Hothior's far west. What's important to remember is that the woods are not just a single adventure ... but potentially more. There's nothing to stop the players from clearing out some of the back country, bringing bandits to justice, searching to uncover the pass that trolls are using to creep through the mountains, or to eradicate a small keep the trolls have built inside Hothior land. Numerous opportunities exist.

Looking at Hothior's norther border, we're brought to

The Invisible School of Thaumaturgy. I don't want to create a post specifically for this small kingdom, so we can discuss it here. In my mind, spellcasting is a guild; one that seeks to protect its secrets, and yet similarly grants those secrets to new members. A mage must learn how to cast somewhere. The school has embassies in every major city, where entry is exclusive — thus only characters with sufficient intelligence and dexterity may obtain an education there.

Politically, the School is a free-lance entity. Positioned between Elfland, Immer, Muetar and Hothior, it can play these off against each other or alternately maintain the peace. It can keep Trollwood strong and a constant threat towards Hothior, Mivior and Elfland, to ensure that the barbarian lands surrounding the School's fiefdom are kept wild. The High Marches form a line of hills that reach down into Hothior, while the Forest of Lurking — truly a more entangled forest than the Bad Axe — keeps Muetar at a distance. The Lowlands of south Immer serve as another frontier. But we will talk more of Immer later.

The Well of Lered is a 50-mile wide lake formed by springs; floods roll down the Flood Water river when ice and snow melt from the High Marches and the unnamed mountains south of the School itself. The Ebbing to the west also forms from these mountains and the hills, and probably further springs throughout.

Hothior would dearly like to seize hold of the upper streams, clear out the barbarians, diminish the power of the School, plunder the forests for timber that could be floated down the Flood Water ... except that the magical power of the School is simply too powerful. Remember, in Port Lork, Lapspell and Tadafat, there are guildhouses dedicated to teaching young Hothiorians to be wizards — and to maintain the School's political status quo. There are like schools in Muetar and Immer. To break the power of the guild, multiple states would have to form an alliance ... and there will always be one state that will fear the alliance once its formed. Mivior can be induced to attack Hothior, the trolls can keep Elfland busy, Pon and Shucassam can be induced to raid into Muetar ... and Zorn, kingdom of the goblins, is an endless headache for Immer.

Thus, Hothior accepts it's northern border, plundering into the forests when it dares, maintaining a watch against the trolls and other barbarians (orcs and such) ... and waits for an opportunity. Perhaps something the players are able to do, as they operate outside the expectations of the game world.

Incidentally, I don't think the School is really "invisible." It's merely hard to reach, and represents an ever-present invisible hand influencing Minarian politics.

Who are the Farnot Seafolk? Nominally, I take them to be an independent guild of sailors and experienced navigators, available as mercenaries and loyal especially to Hothior — who no doubt presses an agreed upon part of their number each year. The Seafolk know the waters of The Sea of Drowning Men and beyond better than anyone in Minaria; they have skills that enable their semi-independence and their protection. Farnot is, itself, unfortified. Their people are scattered far and wide, however, and if another kingdom undertook to destroy the Seafolk, it could be the latter could offer little consequence. Therefore, it's wise not to play favourites. Still, it's possible that through the Seafolk, a tribute is paid by some large distant empire across the sea, who would take unkindly to anything foul. And it would be difficult to track down every last member of the seafolk, to keep news from leaking out.

One benefit of partaking in this exercise of explaining and describing a game world I'll never run is that — while many of these themes are reflected in my game — I'm free to give away details that I carefully keep locked up about my own setting. For example, I have "Schools of Thaumaturgy" in my world ... but how those operate, and even where they are, remains behind closed curtains. The troubles of my own kingdoms are similar, but distinct in their own right, as places like Milan, Gilan, Asmara or Mrauk Oo (a real place) have conundrums far more complicated and levelled than anything I've described here ... because my world is bigger, denser, further elaborated upon and more tangible. Yet Minaria nevertheless serves as a small-scale framework from which the reader can further divise greater complexity.

How would YOU solve the troubles of Hothior's northern border? How would you make better use of the Bad Axe? What arrangements would you try to make with the Farnot Seafolk. How would you approach the Banished Lands. Are you traditional, and unable to see a world beyond the next dungeon door ... or can you see what I mean when I say, controlling this place or that is like acquiring a larger game piece than what your character represents?